In January, two of my best friends from UChicago, Rhea and Joao, came to visit me in Japan! I was so happy to see them, and I am so thankful that they took the time to come visit me.

With friends visiting, I took the opportunity to stay in a more northern part of Okinawa that I haven’t had as much of a chance to explore yet. We stayed in Nakijin, in this very cute, traditional house.

Our first night, we had dinner at Tutan, an amazing restaurant that my cousin Yoko recommended to me. The dining space had the perfect level of dim lighting, and we had some delicious wine and chicken.

The next day, we set off to explore Yanbaru National Park. On the way up, we passed so many motorcyclists wearing matching leather jackets driving up the coast – it looked like an amazing route.

We started off by stopping at some waterfalls, and then got lunch at an amazing sashimi place along the way. It was a fisherman’s shack that has fresh fish every day.

Our next stop was Daisekirinzan, a beautiful area for hiking. It’s believed to be the first place on the island of Okinawa that people considered to be sacred.

It’s a very nice place to have a leisurely walk in the woods and see some incredible rock formations. Although previously called Daisekirinzan, the site has recently been renamed ASMUI Spiritual Hikes. This rock formation was my favorite one along our walk:

Then we went to Cape Hedo, the northernmost point of Okinawa Island. Cape Hedo took my breath away — the jagged cliffs were far more dramatic than I’d imagined.

During the American occupation of Okinawa from 1945-1972, residents would build bonfires here so that the residents of Yoron Island, a nearby island that was still a part of Japan, would be reminded of Okinawans’ presence and aware of their protest against American occupation.

This stone at Cape Hedo commemorates Okinawans’ struggle to have the island returned to Japan following the Second World War:

Although Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, the U.S. still operates a 20,000 acre Jungle Warfare Training Center in the Yanbaru Forest, which is used by the Marine Corps. The non-military area of the forest, about 33,000 acres, was designated a National Park in 2016.

From Cape Hedo, we then headed to Sosu Beach to finish our day-tripping around the park. Sadly we couldn’t go down to the water, but I loved seeing these rocks by the shore:

On the drive back to Nakijin, there was a gorgeous sunset. I had such a fun time on our roadtrip; singing “All I Ask” by Adele at the top of our lungs while driving down the coast with this view will definitely be a lifelong memory.

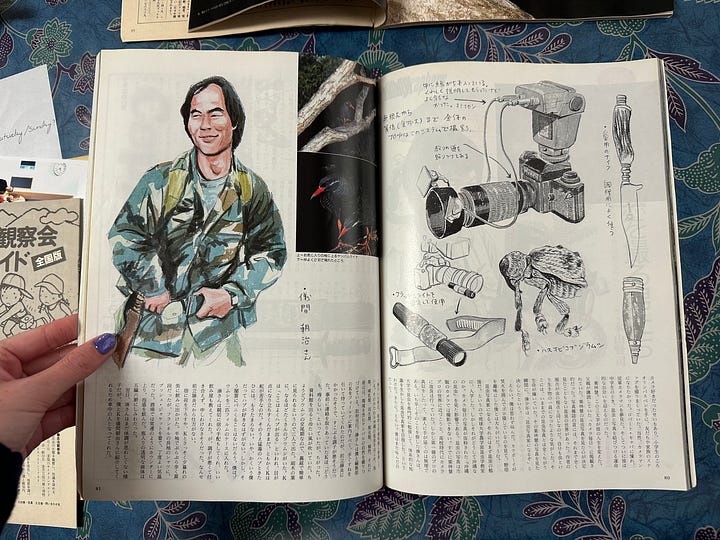

One reason I’ve been wanting to visit the National Park is because of the famous Yanbaru Kuina, a species of bird that is only found in the Yanbaru Forest. I also have a family connection to the animal; my mom’s cousin Tomoharu Gima was the first person to ever photograph the bird, before it was even known as a species.

On a dark April night in 1976, in the heart of the dense rainforest, Tomoharu and his brother Tomoaki were in the Yanbaru National Forest taking pictures. Tomoharu was equipped with his heavy-duty camera lens, almost 5 feet long, while his brother, Tomoaki, held the lighting equipment, illuminating the forest with a stark light.

As they crouched in the brush, the shutter of the camera clicking among the sounds of insects and rustling leaves, they captured an image of a bird with a red beak which they had never seen before. Curious about the name of the bird, they went to the library to identify it the following day, but no such bird could be found in any book or encyclopedia.

Miraculously, this picture turned out to be the first ever image captured of the Yanbaru Kuina, a new species of bird found only in Okinawa. It took another 5 years for the Yanbaru Kuina to be officially designated as a new species, a status that it attained in 1981.

Since then, Tomoharu has become a local celebrity in Okinawa. To say that the Yanbaru Kuina is a symbol of Okinawa and the unofficial mascot of the island is almost an understatement. I see the bird everywhere; on murals, t-shirts, street signs, and posters, and as giant statues outside numerous buildings.

Tomoharu’s legendary photo was featured on the back cover of National Geographic in 1993, introducing the bird as an endangered species:

When Tomoharu’s picture was published in National Geographic, only a handful of Japanese photographers had had the honor of having their photo published in the magazine; Tomoaki told me only about seven had attained the honor before.

Tomoharu was also the first person to photograph the Yanbaru Kuina chick, which is all black:

It makes me smile every time I see a little picture of the Yanbaru Kuina out and about in Okinawa. It’s also amazing how many awesome people are in my family here, and I am so happy to be getting to know them!

After visiting the Yanbaru Forest, Joao, Rhea, and I went to the supermarket and got a bunch of Japanese snacks to try. We got the classics – Meiji Apollo Strawberry Chocolates, Calpico Sticks, and Pocky.

We also tried this crazy thing called Popin’ Cookin’, which is a children’s snack company where you “make” the food yourself. We got these little packets of powder, and when you mix it with water and put it in the microwave it becomes the different components of the burger. We were shocked that the “beef” smelled like real beef, the “buns” smelled like bread, and the “cheese” smelled like cheese. It was honestly pretty disgusting but we were laughing so hard.

In the morning, we went to this cafe right next to our Airbnb called Paramitā (safe to say they had much better food than our microwave concoctions):

I thought it looked cool from the outside, but I was truly blown away once we sat down. There was a beautiful mural on the wall, as well as a mini book store in the corner. The aesthetic, with its artful embrace of raw materials, reminded me of a restaurant I visited in London called the Sessions Art Club.

For lunch, we had a set meal of South Indian cuisine and a delicious strawberry shortcake. I’m so glad we stayed in Nakijin; the beds in our Airbnb were insanely comfortable, and it was so convenient to get to explore the more northern parts of the island.

We then visited Nakijin Gusuku, Yachimun No Sato, Hamabe No Chaya (the beach cafe in Chinen), and ended with a belated birthday dinner for Rhea at Hohobare in Naha. We had so much fun exploring, and I’m so happy that they were able to come to Okinawa!

(I went back to Hamabe No Chaya just a week later, but much to my surprise, the entire cafe is gone! They are renovating it, and the new cafe will be open in March. I was so surprised; the entire structure is gone and not a single beam or plank of wood remains. I am so happy that I took Rhea and Joao here for one last visit to the cafe as it was when my Aunt Niya visited in the 90s).

During the week while I was in class, Rhea and Joao went to Kyoto, and that Friday, I went to Tokyo to meet up with them for the weekend. On the plane ride there, I got this incredible view of Mount Fuji:

On Friday night, my mom treated us to an amazing omakase sushi dinner at Sushi Oya. It was truly incredible; we had multiple different kinds of tuna, as well as an amazing assortment of fish. The uni and scallops were so fresh that they tasted completely different than the flavors I’m used to.

Thank you mom for one of the best meals of our lives!

There were only two other people with us in the restaurant; we were sitting at the counter with them and started chatting, and it turns out that one of them was a UChicago alum! Small world.

The next day we walked around Daikanyama, a very cute, artsy neighborhood in Tokyo. My favorite part was this amazing bookstore that mostly sold coffee table book and other decor-oriented items. I also tried on this jacket, which I didn’t end up buying, but it’s fun that it matches my phone case.

We stayed in an Airbnb in Shinjuku, which was a little out of the way, but not terribly so. Our neighborhood was an immigrant neighborhood, and there were a lot of Nepalese flags in the storefronts on the street outside our place.

Japan has become a very popular place for Nepalese people to immigrate to; Nepalese students constitute the second-largest cohort of foreign students in Japan, second only to Chinese.

I’ve also met a lot of Nepalese people in Okinawa. Nepalese people are the largest foreign working force in Okinawa, and 60% of the students at my school are from Nepal. My school said that the number would be even higher, but that they try to keep the school demographics somewhat balanced. Most of the Nepalese students are trying to learn Japanese to eventually work in Japan, and many of the workers at the konbinis in Naha (7/11, FamilyMart, and Lawson) are Nepalese.

Following the Nepalese Civil War, which lasted from 1996 to 2006, the country has experienced significant political instability; this instability, alongside corruption and natural disasters, have harmed the economy and made it very difficult for young Nepalese people to find work, driving immigration to Japan.

Funnily enough, my friend Lauren was recently living in Nepal as a Pulitzer Fellow, making a documentary about climate change in the Himalayas (specifically how the changing climate is affecting the livelihoods of female sherpa guides in Nepal).

In her film, she highlights how climate change has caused more frequent and unpredictable mudslides, which negatively impacts both tourism and the agricultural industry. This poses a further threat to Nepal’s already fragile economy, which heavily depends on tourism and agriculture.

I have also gotten to know a Nepalese woman who is a teacher at the school that I volunteer at. She has her Master’s degree in social work and her Bachelor’s degree from a Nepalese university, and she moved to Okinawa because her husband got a job as the manager of a taxi service here.

She speaks perfect English and is highly educated, but she said it’s nearly impossible to get a job in Nepal. She explained that, after tourism, remittances—money sent home by relatives working abroad—is the largest source of income for many Nepalese families. She told me that of course she would want to stay in her home country, but that it simply doesn’t make sense for her.

Simply put, Japan needs workers, and Nepalese people need work. Japan’s aging population and decades of low birth rates mean that the country increasingly relies on immigrants to sustain its economy. In that way, Nepal and Japan make a logical match, but it will be interesting to see how Japan, or even the idea of what it means to be “Japanese,” changes over the next few decades as a result.

It’s also fascinating to see how economic and political realities in one country can influence those in another. It’s crazy to me that the circumstances that Lauren is documenting in Nepal, which I would have thought would be so far removed from what I’m doing, actually affects the demographic makeup of my language school in Okinawa.

On Saturday night in Tokyo, Rhea, Joao, and I went out to dinner at an izakaya, where we had amazing fish that they charred with a blowtorch. We then went a bar called The SG Club; Rhea got an amazing cocktail called the Golden Gai.

We sat next to some Americans – three men on a business trip and the much-younger fiancee of one of them – who proceeded to tell us all about their relationship; how they met during Covid when she was working retail, and then he basically stalked her at her job until she gave into going on a date with him, and they broke up multiple times before getting engaged. They were from Tennessee – she’s a songwriter, and she told us about one time when she shared an Uber with Kacey Musgraves. It’s funny the random conversations you have with people when traveling; it’s so easy just to say, “Where are you from?” when you hear other Americans around, and people are almost always very willing to chat; if anything, you learn so much more about them than you would have had you had the same run-in at home.

We then went to a club called womb and ended the night with karaoke in typical Tokyo fashion.

As we were walking from The SG Club to womb, we passed this billboard of Okinawan rapper Awich advertising her brand of habushu, an Okinawan liquor that is made by putting a venomous Habu snake into awamori. Oftentimes, there’s still a real snake in the bottle (there’s even a video of Meghan Thee Stallion trying it).

Awich is one of the most famous rappers in Japan, and she is proudly Okinawan. As a young teenager, she first heard hip-hop music when she picked up a CD of Tupac’s All Eyez on Me. She started turning her poetry into rap, and from then on, she dreamed of going to America. She went to university in Atlanta, where she fell in love with the man who would become her husband – they met when he pulled over on the side of the road to talk to her.

By 19, she was pregnant, and he was in jail for gang-related crimes; in her song “Queendom,” she writes about visiting him in jail, putting her hand to the acrylic and holding the phone to her pregnant belly. Upon his release, they married, but their time together was tragically brief—he was murdered shortly afterward. At just 24, she was a widow and a single mother, and she returned to Okinawa despondent.

By that point, she had given up her dreams of being a rapper and was heartbroken and adrift. It was ultimately her Okinawan heritage that gave her strength after the death of her husband. Her father told her: “You are Okinawan. Everyone lost someone in the war. And yet we live.” I thought that was a really powerful sentiment.

Since then, Awich has become a superstar in Japan – in 2023 she sold out a show at the Tokyo Budokan, and she was also the recent subject of a very well-written GQ magazine feature (I recommend reading it if you want to learn more about her).

In my view, what sets Awich apart is her deep respect for hip-hop as a genre. She has spoken about how Tupac gave her a new language to express the struggles of Okinawans — racial discrimination, colonization, military occupation, and poverty. She often raps in Japanese, Uchinaguchi (the Okinawan language), and English, using her platform to spotlight political issues, such as the U.S. military bases in Okinawa and the island’s marginalized position within Japan.

Her approach to hip-hop contrasts with the stylized rap performances often seen in K-pop, which is very popular Japan. While many K-pop groups include a designated “rapper,” their performances often serve the broader K-pop aesthetic and commercial appeal over furthering the genre’s legacy as a political agent and honoring its roots in Black American culture. Awich, however, is different; she clearly sees rap as an art form and a poetic medium to spark social change and show pride in her heritage.

Her song Queendom recounts her life story, from growing up peering through military fences and having helicopters fly overhead, to moving to Atlanta and processing her husband’s death:

These are some other songs I like:

Awich’s relationship with the United States is complex and reflects a uniquely Okinawan experience. On one hand, she grew up captivated by American culture and music; on the other, she was raised with a deep awareness of the pain the U.S. military presence has inflicted on Okinawa. She grew up attending anti-base protests alongside her parents and heard firsthand accounts from her father, who, in the desperation of poverty, stole cans of soup from American military bases to survive.

In one interview, Awich articulated the layered reality of Okinawa’s relationship with the U.S. bases:

“When you’re a child, you hear kids playing, you see playgrounds on base, and it’s colorful, and it’s big, and people are so outgoing and friendly. We have mixed feelings about that. And that’s Okinawa. Everything is contradiction.” – Awich

I share her sense that Okinawa can be paradoxical at times. To call Okinawans simply “Japanese” is to erase their distinct Ryukyuan heritage; yet, to claim that Okinawans are not Japanese evokes a painful history in which Okinawans were treated as ethnically inferior. To support the presence of U.S. military bases is to condone an unfair burden that echoes colonial imperialism; yet, to oppose the bases raises fears that Okinawa could once again become a battlefield, left vulnerable and unprotected.

These contradictions extend into everyday life. Many Okinawans harbor resentment toward the military’s presence, while counting American service members among their neighbors and friends. And Okinawa, an island rooted in a tradition of peace and nonviolence, paradoxically hosts 32 U.S. military bases that occupy a quarter of its land.

To me, these tensions underscore a simple truth: Okinawa’s story cannot be told without nuance. It is precisely this complexity, this inability to be explained by a single simplistic narrative, that makes Okinawa feel so profoundly human.

In Awich’s music, she writes about the plight of Okinawans – the military presence, the poverty, the pain and trauma – but also the beauty of the island, the strength that her Okinawan heritage gave her after the death of her husband, and the power of realizing that all of humanity is unified as one.

Her song “Tsubasa,” (or wings, in Japanese) is dedicated to the children of Okinawa; she wrote it after the window of a military helicopter fell into the yard of her daughter’s preschool:

The music video for her song “Rasen in Okinawa,” performed with other Okinawan rappers, was shot on the grounds of Shuri Castle, in the Naha nightlife scene, and in a traditional Okinawan home – I think it’s cool to see the blend of Okinawa past and present. The song also uses an Okinawan sanshin, a stringed instrument made with the hide of the Burmese python, and traditional Okinawan folk song melodies:

Awich also often talks about the importance of knowing yourself, which I feel has been a very applicable theme for my time here. It may seem like cliche or even vague advice – what does it mean to know yourself? – but I do think it’s important to take the time to understand what fulfills you, and, perhaps more importantly, have the courage to pursue it.

By living in Okinawa, I feel that I’m not only knowing myself by taking the time to come here, but I am also learning more about who I am as a whole person through learning about my family history and heritage.

Love,

Alexandra ❤️

Bravo for another full and enlightening chapter in your Okinawan-Japanese adventure abroad, Alexandra. From the boatload of input that you are learning, our own vicarious awareness grows through your eyes, ears and pen (keyboard). I imagine that re-entry to the USA will cause a bit of a culture jolt. The night that Nana and I returned home from Finland, among the first words we heard were from someone screaming "EFF YOU!" on a street corner at some other imagined miscreant because ... well, who knows because why? Great to be home again, we thought.

Onward Aloo!

Thank you so much for this soulful and helpful guide to a recent trip around Okinowa. I am exploring the island right now, and your reflections and recommendations are a great help. Off to explore the north and the 'Spiritual Hike' tomorrow. Thanks again. Jody x