Monchu Meeting

A few weeks ago, I attended our family’s monchu meeting. A monchu is an Okinawan clan, and the Gima family is a member of the Shoshi Tamagawa Monchu.

Our monchu consists of the descendants of Sho Kotoku, Prince Yuntanza Chobyo, the 8th son of King Sho Sei (1497-1555), and grandson of King Sho Shin (1465-1527). Our monchu currently has 200 active families and 24 board members, and Tomoaki has been the president of the monchu for 14 years (very impressive!) This monchu meeting was the 50th annual meeting.

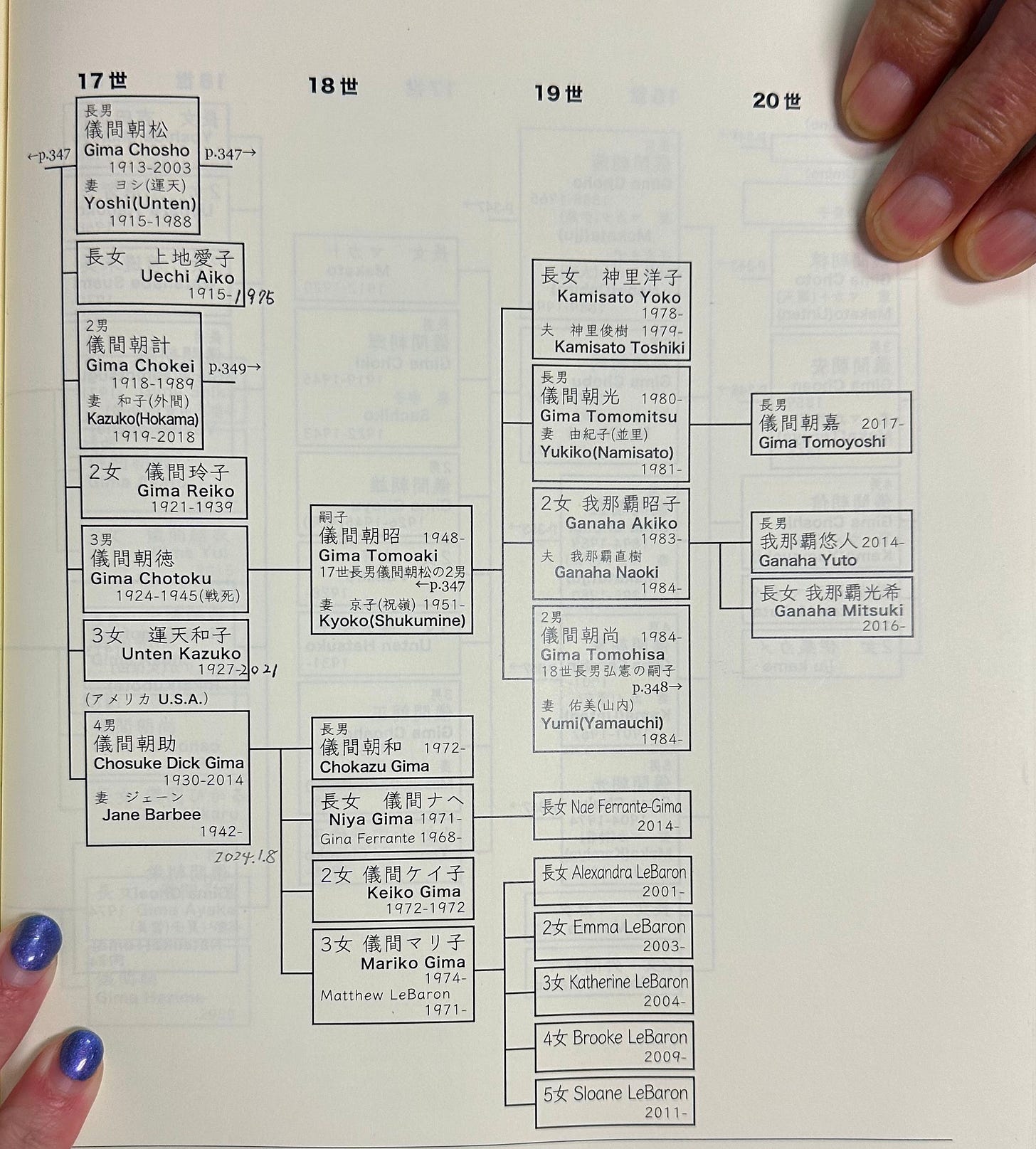

One of the major projects of the monchu the past few years has been updating the family tree book. Following the end of the Ryukyu Kingdom, the records of family histories were treated poorly and damaged, and many genealogies were destroyed during the war. The book was painstakingly put back together starting in 1974 was completed a decade later.

However, traditionally the book has only included male family members. Starting in 2012, the monchu has worked on including female family members. In 2020, the updated book was completed, and my mom, sisters, and I are now in the book, alongside thousands of other relatives.

As a part of the gathering, a monchu member performed karate (see below), and another performed Ryukyu Buyo. I also met an older man, Mr. Owan, who is 93 years old. He was three years younger than my grandpa and was also a student on the GARIOA scholarship. He studied at Penn State in the 1950s, and still speaks completely fluent English. I was surprised how good his English was, as well as how genki he is! It was really cool to be able to talk to him.

During the event, we also had presentation about one of the most famous members of our monchu, Makishi Chochu.

Makishi Chochu was a high-ranking scholar-bureaucrat of the Ryukyu Kingdom during the 19th century. The Ryukyu Kingdom had a caste system, and Makishi Chochu, as well as the Gima family, were pechin, a class of scholar-officials within the upper-class yukatchu. Pechins managed taxation, law enforcement, land records, and trade regulation, as well as diplomacy and defense.

Many pechin families had Confucian-influenced names. My family’s name, Gima (義間), was adopted because the “Gi” kanji (義) means righteousness or justice, a Confucian value. Even today, all of the male relatives in my family use the same kanji in their individual names, another traditional pechin naming practice. Their kanji, 朝, can be pronounced in one of three ways – Cho (meaning dynasty), Asa (meaning morning), or Tomo (phonetic pronunciation) – which is why all of my male relatives have names starting with one of those prefixes (Chosuke, Tomoaki, Asanori, etc.) The kanji 朝 was often used by aristocratic and royal families during the Ryukyu Kingdom due to its connotations of dynasty.

Pechin were also highly educated, trained in Classical Chinese language, literature, and ethics, as well as Classical Japanese for diplomacy. Each year, four Ryukyuans were permitted to study at the Imperial University in Beijing, the highest educational institution in China. Furthermore, 2-3 pechin would be selected annually to study in Fujian at the Confucian academy for tributary students, where they would live in the Ryukyuan embassy.

Makishi Chochu was one of these pechin. While studying in China, he witnessed the First Opium War. Seeing the Qing Dynasty defeated by Britain, he realized that the Ryukyu Kingdom, lacking an army, would need to increase its diplomacy with the Western world to maintain its power. As a result, he devoted himself to learning English and French. He was thus fluent in five languages: Uchinaguchi (the Okinawan language), Chinese, Japanese, English, and French.

Makishi Chochu’s observation about the growing power of the Western world proved to be quite prescient – he is perhaps best known for negotiating with American Naval Commodore Matthew Perry during Perry’s visit to the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1853, leading to the signing of the Ryukyu-US Treaty of Amity in 1854.

However, his career was derailed by the Makishi-Onga Incident, in which he was accused of bribing two Japanese samurai in Satsuma to influence his election to the Sanshikan, the kingdom’s council of top advisors. This, however, was a false accusation – Satsuma had become frustrated with Ryukyu’s increasing trading ties with France, which Makishi Chochu had been leading. Satsuma officials found an official willing to accuse Makishi Chochu of bribery, and he was sentenced to exile in Yaeyama Island for 10 years. However, after 7 years in Yaeyama, he was pardoned and allowed to return to Shuri.

A few years after his pardoning, Makishi Chochu was ordered by Satsuma to become an English teacher in Kagoshima. However, he decided that he would rather die than work for his detainers; on the boat ride to Kyushu, he jumped into the ocean, committing suicide.

Despite his tragic demise, Makishi Chochu is still regarded as one of the most distinguished and successful diplomats in Ryukyu history. It was really interesting to learn more about him and our family at the monchu meeting.

The Life Story of Nakahama Manjiro

In addition to Commodore Perry, another famous person Makishi Chochu interacted with was Nakahama Manjiro, whom he interrogated when he first arrived in the Ryukyu Kingdom. I’m going to take a slight digression because I find his story fascinating, and I hope you enjoy learning about it too!

Nakahama Manjiro was the first Japanese person to live in the United States, and his life is the closest thing I’ve ever heard to The Odyssey in real life. His journey began as a 14-year-old boy marooned on a deserted island, and his eventual return home took him through the Kingdom of Hawaii, the whaling industry of New England, the California Gold Rush, the Ryukyu Kingdom, and, after more than a decade away, finally back to Japan.

Manjiro was born in the small Japanese village of Nakanohama in 1827. His father died when he was only nine years old, and to support his family, he became a fisherman. At 14, he set out on a fishing trip alongside four brothers, which was only supposed to last a couple days. However, they were caught in a storm, losing their sails, oars, and rudder. After being adrift for days, with powerful currents carrying them far out to sea, they eventually washed ashore on the uninhabited island of Torishima, where they survived for months by eating the albatross on the island.

One day, they finally caught sight of a ship; it ended up being an American whaling ship captained by William Whitfield of Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Captain Whitfield and his crew rescued the boys, but at the time, leaving Japan was a crime punishable by death, and American ships were not permitted to enter Japanese harbors, so the crew was unable to bring them back to Japan.

As a result, the boys stayed with the John Howland until the ship reached Oahu, then part of the Kingdom of Hawaii. While the others found work in Honolulu and chose to remain, Manjiro – whom the whalers had nicknamed “John Mung” – decided to continue on to New Bedford with the crew. Captain Whitfield had especially bonded with the boy; he had been teaching him English and was impressed by his intelligence.

After more than a year at sea, the crew arrived in New Bedford, where Captain Whitfield took in Manjiro as his foster son. Manjiro attended school in Fairhaven, learning English, navigation, mathematics; he also learned barrel-making while working as a cooper for the town’s whaling industry.

While Manjiro became deeply integrated into the community in Fairhaven, he longed to return to Japan, especially to see his mother. However, the journey back would not be easy. After working on a whaling ship for three years – which also allowed him to visit his friends in Hawaii – Manjiro heard about the California Gold Rush and thought it was the best opportunity to earn the money needed for his return to Japan. He set out for San Francisco, and after just 70 days in Sacramento, he successfully mined $600 worth of gold – more than he had earned in three years on the whaling ship, where he had made only $350.

After that, Manjiro set sail for Hawaii, where he was once again reunited with his friends. One had since passed away from complications related to injuries sustained in their initial shipwreck, while another had settled into life in Oahu and wanted to stay. The remaining two, however, decided to return to Japan with Manjiro. The three men set sail on the American merchant ship Sarah Boyd, which was heading to Asia.

To re-enter Japan safely, they devised a plan: instead of heading directly to the mainland, they would first land in the Ryukyu Kingdom, allowing them to gauge the Japanese authorities’ response without violating the country’s strict isolationist policies, which were still punishable by death.

They rowed ashore to the Ryukyu Kingdom on February 2, 1851, a full decade since their initial shipwreck. The Okinawan locals were taken aback by their foreign clothing, but Manjiro and his friends were offered hot, steamed potatoes. Grateful for this kindness, Manjiro and his friends then prepared beef and coffee for them.

Manjiro and his friends were then placed under house arrest and interrogated by Makishi Chochu, my distant relative, who was serving on the Sanshikan at the time.

Manjiro had brought with him a number of items to teach isolated Japan about the Western world, including a navigation manual, mathematical books, a map, an octant, a compass, a pistol, and a biography of George Washington. During their interrogation, Makishi Chochu took a particular interest in Manjiro’s copy of George Washington’s biography (apparently, Commodore Perry was surprised by Makishi Chochu’s depth of knowledge of the United States when he came to Ryukyu the following year).

As a part of their interrogation, Manjiro and his friends were given bowls of rice and chopsticks to test if they were truly Japanese. Manjiro and his friends were then transferred to Naha, where they were further interrogated by Satsuma officials. After one month of interrogation in Ryukyu, the Japanese transferred them to Kagoshima for more questioning.

They also underwent a religious test, where they were asked to walk on a Bronze plate of the Madonna and child to prove that they weren’t Christian – this was also an offense publishable by death in Japan. After a few more months, the Japanese decided that Manjiro and his friends had not purposefully intended to leave Japan, and that their extensive knowledge of the Western world would be an asset, so they were not punished.

On October 5, 1852, Manjiro finally returned to Nakanohama, where he was reunited with his mother. She had presumed him dead and even made him a gravestone, assuming he had been lost at sea many years prior. He was elevated to samurai status and later became a translator and diplomat, and he also taught Western shipbuilding at the Naval Training School in Nagasaki.

I just thought that this story was truly incredible. It’s crazy to think of all of the different places that Manjiro went, and it’s also cool to see how my family plays a small part in his story!

Yuimaru Culture

It was a great experience to meet so many of my distant relatives and learn more about the history of the Ryukyu Kingdom at the monchu meeting. It’s really beautiful to see the immense care and dedication that has gone into preserving our family’s monchu lineage.

The Okinawan monchu is, in many ways, a reflection of the Okinawan spirit of yuimaru, or mutual aid and community support. Unlike Japan’s ie familial system, which is hierarchical and follows a strict patrilineal structure from father to son, the Okinawan monchu is collective, emphasizing unity among extended family members.

In college, I did a research project on the economy of the state of Hawaii, and I was surprised to learn that Okinawans are the most economically successful ethnic group in the state. This discovery was particularly surprising to me because, growing up, I had always heard about Okinawa’s economic disadvantages within Japan.

Part of the reason that Okinawans have fared so well economically in Hawaii is because of yuimaru culture. After Okinawa was taken over by Japan, the island became impoverished, driving many Okinawans to become sugar cane laborers in places like Hawaii. When Okinawans first arrived, they were discriminated against by Japanese immigrant groups, being called names like “pig-eater.” However, Okinawans looked out for each other, creating credit unions and mutual aid groups. Since then, Okinawans in Hawaii have been particularly successful in the food industry; brands like Zippy’s, King’s Hawaiian, and Times Supermarkets were all started by the children of Okinawan immigrants. Looking at the data, it’s truly striking to see how successful the Okinawan community in Hawaii is in every metric.

This emphasis on family and community also extends beyond the monchu. Okinawa has the highest birthrate in Japan, and the general vibe on the island is much more laid back and welcoming than the mainland.

The difference in openness between Okinawa and Japan is true in a historical sense –Japan was historically an isolated nation, while Ryukyu was an open trading nation – but I think this is also true when it comes to spirit and personality. Where as being “Japanese” has historically been exclusionary (today, even fully-ethnic Japanese nikkei living abroad might not be considered “Japanese”), Okinawa is much more inclusive. I’ve had many older Okinawan people tell me, “You have Okinawan blood? Oh, so you are Okinawan then.”

It’s really interesting to learn more about the history of Okinawa, and then see those historical structures play out in present-day interactions, culture, and societal trends.

Lunar New Year

The Wednesday following the monchu meeting, I celebrated Lunar New Year with my family. Okinawans have traditionally followed the Lunar Calendar; since reversion to Japan in 1972, the tradition of celebrating Lunar New Year in Okinawa has slowly diminished, but my family still celebrates. Tomoaki told me about how when he was a child, as a part of Lunar New Year, all the children would go to the front doors of different houses in their neighborhood with little pails of water, and they would get coins in exchange. It kind of sounds like Halloween!

We started off the night by blessing the food at the family altar. Traditionally, Okinawan homes have a Bhuddist altar, called a Ryukyu Bustudan, to honor their ancestors. I brought special strawberries from the Nara Strawberry Lab, which were red, pink, and white, and we also ate an assortment of different Okinawan foods.

To celebrate, we got together with Tomoaki’s son and daughter-in-law and their 6 children, as well as Tomoharu and his wife, and their son and daughter-in-law, who have 8 children. These two Gima families share a backyard in Chinen, and between them they have 14 kids, 11 of which are boys. They said that everyone in their school knows the Gima family, since there are so many of them. It’s such an idyllic way to grow up – sharing a backyard with your second cousins, running around the neighborhood.

One of my favorite parts about Chinen is that every night at 6:00pm, a soft melody plays in the streets, alerting all the neighborhood kids playing outside together that it’s time to go home for dinner. That idea is so sweet that it almost makes me cry every time I hear the bell ring:

After our Lunar New Year dinner, I got to play with the kids! It was so nice to meet Tomoharu’s grandchildren. I spent a lot of the time playing Legos; we built a house, and then Chozen was very intent on having me help him construct his electric Lego train. The kids were also enjoying trying to catch marshmallows in their mouths.

The older boys played on their Nintendo switches, and then were doing the thing where you try to flip a plastic water bottle and have it land right-side-up. It’s cute to see how childhood is pretty much the same everywhere you go.

Later that week, as a part of the Lunar New Year, I joined the members of our monchu on a tour to pray at seven different worship sites. We started st Shuri Kannodo, a Buddhist temple, and then we went to Tamaudun, the royal family tomb. Our next stop was Uryu Hija, a sacred dragon-shaped spring at Shuri castle built by our ancestor, King Sho Shin. That spring provided the water to the royal family, and that used to be the spring that all awamori had to be made with.

Then we went to Sakiyama Utaki, a sacred grove, and Sashikasa Hija, a spring discovered by Princess Sashikasa Jinganasi, the eldest daughter of King Sho Shin, our ancestor. That was probably my favorite – we had to walk down an enchanting moss-covered stone stairwell to reach the spring. We then went to Bengatake Uka, a sacred spring, and finished at Bengatake, a sacred hill.

It was so nice to join on this traditional journey! It’s also really special to see how much ancestor worship and awareness is built into the culture in Okinawa. Remembering where you come from, where your family is from, and connecting with your community can have really beautiful results.

It’s already March, which means my time in Okinawa is coming to a close this month! But since it’s taken me a while to write about everything I’m learning about, I still have lots of ideas for future newsletters about what I’ve been up to :)

Love,

Alexandra ❤️

Some other interesting things I learned about Nakahama Manjiro:

Manjiro became extremely close to the Whitfield family while living in Fairhaven. In one account I read, when the Whitfields’ church insisted that Manjiro sit in the pews designated for people of color, separate from their family, the Whitfields switched to the Unitarian church. One of their fellow congregants was Warren Delano II, the grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In a 1933 letter to Manjiro’s son, FDR wrote: “I well remember my grandfather telling me all about the little Japanese boy who went to school in Fairhaven and who went to church from time to time with the Delano family.” Warren Delano II made his fortune smuggling opium into China, directly leading to the First Opium War.

After returning to Japan, Manjiro saw Captain Whitfield one last time in New York, 20 years later, while en route to England on behalf of Japan. Today, a museum in Fairhaven is dedicated to Manjiro’s story.

This is so fascinating, Alexandra. I imagine that soon after your return you will visit the Manjiro-focused Museum in Fairhaven. If you do, maybe Nana and I would like to join you there. Small world: what an astonishing link between the family and FDR, perhaps putting in sharper relief that public speaking project you did at NCCS on FDR. Enjoy, and capitalize fully, on the time remaining in your Odyssey. You have given your readers a rich trove of narration and imagery for our own vicarious enlightenment. Love, Papa

This is so cool aloo!! It's so interesting to read and you're such a good writer. I loved reading about everything. I miss you so much!! I love you ❤️